Then & Now: Penny Pitou’s Olympic silvers led to a lifetime of gold

Author’s note: When I was seven, mom put the 1960 Olympics from Squaw Valley on television for me. I was hooked. I can still remember Penny Pitou racing down KT22 to win Olympic silver. It was my introduction to ski racing and led me to a long career in the sport. Penny embodies the passion we all feel about skiing and being outdoors in the mountains. Even today, she still chases her U.S. Ski Team granddaughter around the slopes from Gunstock to St. Anton and takes tour guests on high alpine ridges. This is the story of Penny Pitou, but also a story of ski racing in the post-war ‘50s and the formation of the roots we know as our sport today. – Tom Kelly

A forlorn 17-year-old trudged through the streets of Cortina d’Ampezzo, skis on her shoulder and a sad look across her face. It had been a long season leading up to the 1956 Olympics. She had landed in Europe over two months earlier – her first time ever overseas! But now it was time to call it quits.

She walked into the elegant old Hotel Bellevue in Cortina’s Centro Storico – quite a prestigious place for a young girl from the Belknap Mountains of New Hampshire. At a table sat Vermont skiing legend and two-time Olympic champion Andrea Mead Lawrence – her idol. The young girl slunk over to her.

“How did you do,” said Mead Lawrence, bringing a tiny porcelain cup of hot chocolate to her mouth. “I fell,” said the young ski racer, looking down at the table. “I’m not going to do this anymore. I’m just going to go back home and then go to college. I’m just, well … this is it.”

Mead Lawrence never flinched. “Well, that’s interesting,” she said, calmly taking another sip of Italian chocolate. She looked the ski racer in the eyes and said, “I understand that if you hadn’t fallen at the finish you would have had the fourth fastest time today.”

The young girl’s eyes got big. “I did?” she asked.

“If I were you,” said Mead Lawrence, “I’d stick with it.”

It was a short conversation. Today, 64 years later, the ski racer remembers every single word. It was two minutes of simple advice that changed her life forever.

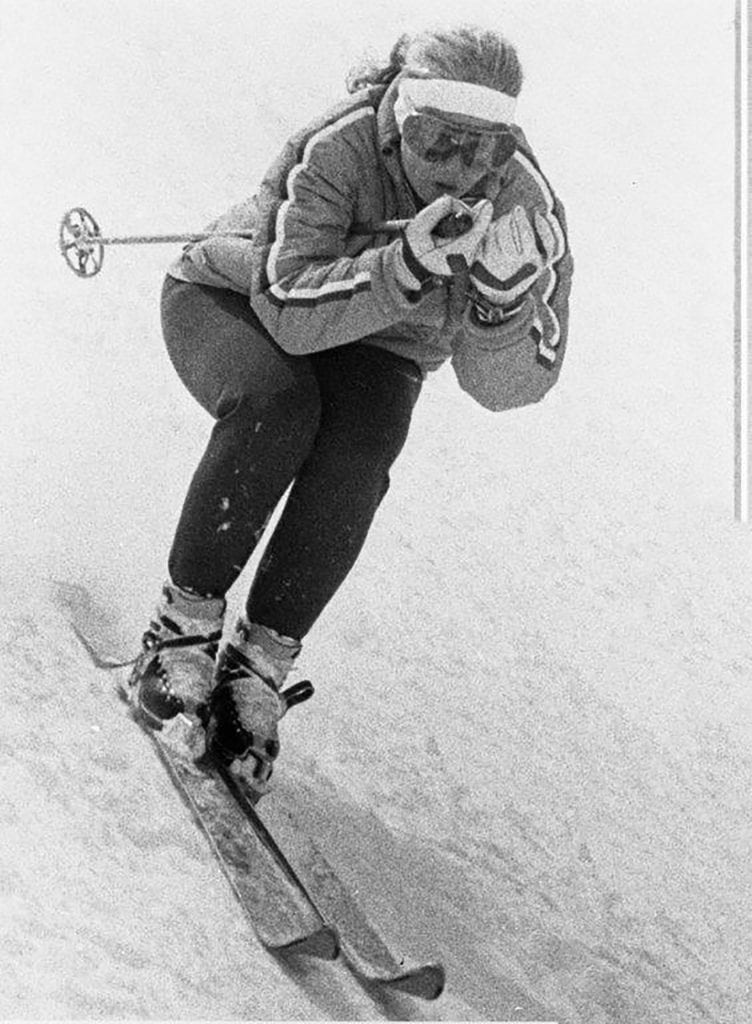

Penny Pitou, a bright-eyed, blonde-haired beauty of a ski racer from Gilford, New Hampshire would go on to win two Olympic silver medals four years later and capture the hearts of America along the way.

The vivacious Pitou became the sweetheart of skiing in the 1950s and ‘60s. She then turned it into a lifetime of hospitality through her Penny Pitou Travel, continuing today to escort skiers and hikers to her adopted homeland across the peaks of the Alps. At a young 81 (turning 82 on Oct. 8), she still doesn’t miss a beat, continuing to regale her guests on mountain alpine trails and cheering for granddaughter Zoe Zimmermann on the U.S. Ski Team.

How It All Began

Life is often defined by choices and circumstances. Born on Long Island, Pitou was a long way from ski country. But when she was three, her father decided to move the family to New England.

As a young boy, her father’s family had vacationed in New Hampshire, staying at a cabin near Laconia. He fell in love with Lake Winnipesaukee. “One day he said, ‘I want to be a farmer and live up there in New Hampshire,’” said Pitou. So they packed the family and headed north, settling in Center Harbor on the north side of the lake.

“He didn’t know one end of a cow from the other,” laughed Pitou. “He went around to all the different farmers and asked them what kind of cattle he should get and where you should milk them. But, eventually, he caught on.”

They lived on the farm for five years. “Then my father realized that farming was not going to help him support his family,” she said. “So we moved to Gilford and that’s where it all really started.”

Before coming to Gilford in 1945, Pitou had skied a few times. It was mostly barrel staves and leather straps tied to galoshes. “I could barely keep my foot in and they sent me down the hill,” she recalls. “I didn’t make it but it was kind of fun.”

In Gilford, the Pitous found other outdoor-oriented families who shared their interests. With the end of World War II, around a dozen new families moved to the tiny town on the southwestern side of Lake Winnipesaukee. It was new New England meeting old New England, as one family described it. The new families, who came from around the east, found a welcoming home in Gilford. They all shared a love of the outdoors and a desire to explore and be free after years of the constraints of war.

Penny’s father, Gus Pitou, worked with local sportsmen, Gary Allen and Marty Hall, Sr., to start the Gilford Outing Club on a small slope along Schoolhouse Hill Road. The Pitous lived on Potter Hill Road, at the top, so young Penny could just strap on skis and slide right down for her first run of the day. An old ‘two-holer’ outhouse became the warming shack at the top.

“These families all had young kids,” she said. “There were no organized sports of any kind! So they decided to give kids something to do in the wintertime – skiing or skating.”

The families all chipped in to buy an old Ford Model T, mainly to get the engine. Hall, Sr. figured out how to get it to work. They talked a farmer into letting them use his pasture as a ski hill, putting up some poles and stringing a rope up through the trees to create a rope tow.

“They got it going,” said Pitou. “I was eight at the time. We would walk from school down the main street in Gilford with our skis over our shoulders, taking the rope tow up to practice one or two afternoons a week.”

Pitou joined a rat pack of kids who just loved being outdoors – boys and girls playing together in a wholesome way. They created their own fun from kick-the-can games to hanging a zip line with an old rope or a tarzan swing in a barn. They would meet at the village store owned by Dick Taylor’s father and ride their bikes to Lake Winnipesaukee to swim or fish. They played tackle football together, boys and girls. Penny was the ultimate tomboy.

In the winter, they would ski together all day, taking breaks when Seth Keller would bring out ice cream from his store in town for them. They made laps on the rope tow hill or head up to Gunstock on Belknap Mountain. It was an idyllic childhood the kids created for themselves in a period when America was reawakening from the war.

“What was really amazing was that each of the 10 fathers was so different and brought something unique and special to the group,” said Marty Hall, Jr. Of the pack of kids who spent their childhoods together in Gilford, three went on to the Olympics. Pitou competed as an alpine skier in 1956 and 1960, while Dick Taylor was a cross country Olympian in 1964. Marty Hall, Jr. went on to coach at five Olympics for the USA and Canada, playing a pivotal role in the success of Vermont’s Bill Koch who won Olympic silver in 1976.

Allen, a PanAm pilot who had first discovered skiing at the 1932 Olympics in Lake Placid, would prove to be a guiding light for young Penny. A tireless volunteer, he served as a coach, of sorts, for young junior ski racers. He came up with his own skills test, awarding athletes with a chevron for each test they completed.

A next door neighbor to the Pitous, Allen had five kids of his own, but also took Penny under his wing. “He became my sort of quasi-coach,” she recalled. “He would set up these slalom courses with birch trees. I guess I got through the course enough in one day for him to say, ‘well, you know, let’s go to a race.’”

There were not a lot of women racing back in the early ‘50s. Pitou remembers fields of 10, maybe 15 on a big day. “It was not like the ninety to one hundred my granddaughter races against today,” she said.

Budding career as a ski racer

From her early days as an eight-year-old schussing from home down the Gilford Outing Club hill and nearby Belknap (later Gunstock), to her high school years at Laconia High, Pitou became a ski racer with all around skills. She learned how to jump and she skied fast – a downhiller in the making. There weren’t many women in the sport, but she didn’t care. She was one of the boys.

“I raced with them and there was no big deal,” she said. “I grew up with these boys. We played in the woods, we built tree houses, we went exploring. We would go over the mountains to go to the motorcycle races so we wouldn’t have to pay.”

Together, they found a love for the snow. They skied downhill, cross country and ski jumped. Penny was a better ski jumper than most of the boys.

There wasn’t a women’s ski team at Laconia High so Pitou was on the outside. “I was one of the best skiers in Gilford,” she stated. “At least I could go fast. And I was a jumper. They all went out one day and said, ‘we’re going to go, we’re on the same team.’ I said, OK, I’ll come, too.” She took on the name Tommy, tucked her hair into her hat and joined the ski team.

“I never thought that I shouldn’t be doing it because I was a girl.”

But all came, well, unraveled at a race in North Hampton. Pitou loves telling the story.

“It was a GS and I was going lickety split,” she recalled. “But, I can tell you, my turns were not reliable. I came screaming down and I tried to get around this gate and I caught an edge, fell flat on my face, right in front of a gatekeeper.

“My hat came off and my hair fell out and this guy looked down at me and he said, ‘oh, my God, it’s a girl.’ And that blew my cover.”

Two weeks later Pitou, then a freshman, was called to the principal’s office. “He said, ‘Penny, I have to talk to you about the ski team.’ And I thought it was going to say, you know, you’re doing a great job on that team. We were one of the best in this area. But he didn’t say that.”

Instead, the principal asked her to leave the team, ostensibly under the pretext of parents not wanting their boys to be riding on the bus with a girl and no chaperone.

“Chaperone? I mean, I’ve played with these kids for seven years – half of my life. And now I need a chaperone to ride on a bus. I never understood that. It still ticks me off, you know? So they kicked me off.”

Pitou’s breakthrough came in 1955 at the Junior Nationals in Whitefish, Mont. Her neighbor/coach Gary Allen collected 50 cent donations around Gilford, raising $450 to send her to the event, held at the relatively new Big Mountain ski resort, which had a thriving race program. She boarded a Northwest Airlines propeller aircraft for the long cross country journey to Flathead County Airport near Kalispell.

“What a shock it was to go to Junior Nationals,” she reminisced. “I just stood on the hill and watched the other teams. They came in with their special parkas and coaches. It was almost like the days when we didn’t have anything and I didn’t know what I was doing. So I just stood there. I would watch them go down. And when I thought they were maybe far enough down and wouldn’t see me, I would follow in their trails. And that’s how I would train for the downhill.”

On downhill day Pitou took her secretive learnings along with her Northland skis and headed to the start. “I went lickety split,” she said. “I got down. I didn’t fall.”

In those days, it could take hours for times to be recorded and announced. So Pitou left. Three hours later, she came back to watch a woman on a stepladder putting numbers and names up on the board.

“I looked at her putting up the start numbers and wasn’t sure why my number was on the top, so I asked her ‘why are you putting them in that order?’” said Pitou. “The woman said to me, ‘well, that’s the order in which they placed. Some kid from New Hampshire named Penny Pitou won.’ What a shock that was. I just told her, ‘well, that’s me!’”

The next day, Pitou went out onto an iced slalom course with no offset edge on her wooden Northland skis. She won again.

“I have no idea how I did it, but I did it because I was determined,” she said. “You can have a lot of talent and not be determined, or you can have a lot of determination and not much talent. And sometimes that wins.”

She arrived back in Gilford carrying a bundle of trophies. “My mother said, ‘why don’t you go to see the Olympic team (at an event in North Conway, N.H.)?’ I said, ‘oh, my, you know, I’m only 16. I can’t do that? But she reminded me that Andrea Mead Lawrence (who three years earlier had won two Olympic gold medals) would be there. She was my idol, my hero, my everything – from then right up to the end of her life. She was the person that I wanted to be just like. So I went.”

Those races in 1955 were a breakthrough for the young teen – not so much for her own results, but for showing her the top level of the sport.

“I watched Andy in the starting gate, how she handled people, how she talked to the press and of course, her skiing,” said Pitou. “I came home and I said, ‘oh, that was wonderful. That was the best thing I’ve ever done, is to watch her, to see her, to actually meet her.’”

Her mother reminded her of the upcoming Olympic team trials in Stowe, Vt. It took a little more encouragement from mom, but eventually her daughter decided to go. Allen took her on the four-hour drive to Stowe.

“We got to the start of the Nosedive where they had the seven turns in those days. And it was pretty damned icy. I wrapped the long thongs around my boots, which were like hiking shoes.”

Once strapped in, Allen asked her to unstrap and give him her skis. He got out a pen knife and started to carve an offset edge into the wood. “I said, ‘what are you doing? I can’t afford seven dollars for another pair of skis!’” But Allen knew what he was doing. And it worked. Pitou finished as fourth American and fifth overall. Her idol, Mead Lawrence, won the slalom and giant slalom, and tied for the win in downhill.

But she hadn’t yet earned a ticket to the Olympics in Cortina. It took another stroke of fate. There had been some controversies between the National Ski Association (later USSA) and the U.S. Olympic Committee over the selection criteria that almost resulted in Buddy Werner being dropped from the men’s team. According to USSA records, to resolve that matter, the Olympic Selection Committee agreed to an added team spot for Bill Beck. Janet Macomber, the chair of the NSA’s Women’s Skiing Committee, stood up and said “if you add a man to the men’s team, you should also add another woman.”

Shortly after that, Penny Pitou received a telegram informing her that she was to fly to Europe. She was going to the Olympics.

“I was just sixteen at the time – a senior in high school,” she recalled. “I left home in late November. Oh, man!”

While Pitou never confirmed who it was that stood up for her in that meeting, she’s always acknowledged that it was Macomber. Janet was the matriarch of the Macomber skiing family and a big advocate for women.

“My grandmother was definitely heavily involved back then,” said Jory Macomber, former coach at Holderness School and Burke Mountain Academy. “She drove the women around to races, got them training and entered into races.”

“She was very involved in junior racing,” said Pitou. “I never knew for sure who it was who stood up for me. But it was just an unbelievable, fabulous experience for me to be able to go to Cortina d’Ampezzo when I was just 17 years old.”

With the Olympic season looming ever closer, the NSA struggled to meet its proposed $56,000 budget to fund the team through the season. By November, it had raised only $30,000. National magazines like Time and Life ran huge spreads to promote the team. In late November, the team headed to Europe for the Olympic winter.

Beginning a love affair with Europe

On a dark late fall evening, the teenager settled into her seat on a PanAm for what was then around a 14-hour flight to Europe on an old DC-6 four-engine propeller aircraft.

“As soon as I landed in Zurich, I knew I’d come home,” she said. “I mean, I loved the way it smelled. I loved the food, everything about it. I was never homesick in Europe and I’m still not homesick when I go to Europe because that’s what I do for a living.”

Imagine, now, a 17-year-old girl from a small town in New England traveling Europe for the very first time. She was captivated by the cragged mountain peaks of the Swiss Alps, comforted by the tiny Austrian villages in the Tirol and mesmerized by the first rays of sunlight on the red rock of the Dolomites surrounding Cortina d’Ampezzo.

She trained with the team in Cortina and traveled to magical places to race. While the men contested the Lauberhorn in Wengen, the women were on the other side of the mountain in Grindelwald.

“It was a short downhill, but it was steep on the top – three big turns and then down into the woods,” she recalled. “And you just better make that turn into the woods or you’re dead. There were no control gates, just the trees.”

Until 1962, the women raced the Hahnenkamm in Kitzbühel, just like the men. Mid-January, the U.S. women headed to Austria. Pitou was 51st in the downhill on a day the USA was led by Gladys ’Skeeter’ Werner.

“I wasn’t spectacular, but I managed to get through those courses,” said Pitou “In Kitzbühel I did fall in the downhill and screwed up my knee a little bit, but not enough to keep me out of the Olympics.”

It was a U.S. team in transition. Dorothy Surgenor from Stevens Pass, Wash. and Mead Lawrence were 24 and Werner 22 – older by women’s standards of the day. Pitou and Vermont’s Betsy Snite (later Riley) were just 17, future stars who were soaking in the experience of being with the veterans.

“It was just a thrill to have Andrea Mead Lawrence as a teammate,” said Pitou.

The women’s Olympic course in Cortina started on a steep, wide open slope, with skiers taking a few broad turns before shooting into the woods. The men skied a separate course on the Olympia delle Tofane, where the women’s World Cup runs today.

In her Olympic downhill debut, she finished 34th out of 44 finishers, 18.2 seconds behind gold medalist Madeleine Berthod of Switzerland. Werner was 10th; Mead Lawrence finished 30th. She was also 34th in giant slalom and 31st in slalom.

Women’s ski racing in ‘50s

After graduating from Laconia High School in spring of 1956, Pitou enrolled at Middlebury College, balancing school with ski racing. It was a delicate balance. And Europe beckoned. Competitive as she was, she wanted to make the dean’s list. But more important for her was making the 1958 World Championship Team to compete in Bad Gastein. She skied domestically in 1956-57, making the 1958 worlds team by an eyelash. She was the last to be chosen.

In 1957, she set aside school, hopped on an airplane to Europe that November and stayed until March, 1959. Without the benefit of coaches or team managers, she made a life for herself in Europe for a year-and-a-half.

With the exception of Gary Allen, who shepherded Pitou when she was young, coaches didn’t play a big role in her career.

“We really coached ourselves,” she said. “I don’t really remember ever having a coach tell me what I was doing wrong or doing right. “Betsy and I were very young and there were more important people to be coaching at the time.”

Pitou recalls one time when a coach got on Snite, telling her, “if you don’t shape up, we’ll put a postage stamp on you and send you home.”

One of her early coaches was the legendary Friedl Pfeiffer, an Austrian who grew up in St. Anton am Arlberg before moving to Sun Valley and later Aspen. “Betsy and I were only 17 and he looked down on us because he said we wouldn’t follow the rules and I couldn’t turn.” Why turn, thought Pitou, who loved racing downhills.

Snite, who traveled with Pitou during that winter of 1955-56 in Europe, was one of the early influencers on her competitive career. The Norwich, Vt. native was the ideal wingman for Pitou, especially when they decided to spend her winters racing in Europe in the leadup to the 1960 Olympics.

“She became my roommate for all the years that we were racing in Europe,” said Pitou. “She was a terrific roommate. She would sew on my buttons and I would put up with her smoking. She was a swinger, my friend Betsy.”

Snite hated to train but was still the best skier on the hill. “She could really turn,” said Pitou. “Her job was to win slaloms and my job was to win the downhills – we had a deal.”

Once Snite beat Pitou in a downhill and came back to the room and asked sarcastically, “oh, Penny, did you fall down?” Pitou laughs about it today. “Betsy, you know the deal – you win the slaloms, I win the downhills!”

Another good friend was Renie Cox (now Gorsuch), who came out of Port Leyden in western New York. “We met early on, maybe when I was 12 or 13,” recalled Pitou. “We went on to ski together at Junior Nationals in Whitefish and we’ve stayed friends ever since.”

It was also a time of an equipment revolution. No sooner had young Penny landed in Europe than Anton Kästle approached her personally to ski on his Austrian skis. “I loved Mr. Kästle,” said Pitou, who found extra work at the Kästle factory in Hohenems, near Bregenz in western Austria. “He used to come in to work on his bicycle in his lederhosen. He was terrific. I started with Northlands and he gave me brand new skis just before the (1956) Olympics. Everybody was skiing on Kästles.”

By the time of the 1956 Olympics, skis with offset edges were common. A year earlier, they were screwed in. There were no releasable heel bindings, but German Hannes Marker had started his binding company four years earlier and was providing releasable toe pieces.

“All I ever saw was the top of Mr. Marker’s head because he would be at the starting gate of every race adjusting a little piece of his Marker toe piece for the racers. He worked his fanny off.”

The 1959 season was a real coming out for the fledgling American ski team.

Pitou had a breakthrough, finishing second in the 1959 Hahnenkamm. She then went back to the finish to watch the men where American Buddy Werner was taking on a star-studded field of legends including Swiss Roger Staub, French downhiller Jean Vuarnet and Austrian favorites Karl Schranz and Anderl Molterer.

“Betsy and I both came to the finish line to watch Buddy,” said Pitou. “He didn’t speak German so when the announcer was giving the times and I would translate. I told him, ‘Buddy, you won. You won this thing!’”

Werner became the first American man to win the Hahnenkamm downhill, and the only one until Daron Rahlves became a Hahnenkamm sieger in 2003.

Over the 1959 and ‘60 seasons, the first U.S. women’s power team was developing. Pitou and Snite were joined by Cox, Linda Meyers of Mammoth Mountain, Joan Hannah from Franconia, N.H. and Bev Anderson who skied out of the tiny town of Mullan in northern Idaho. While Gretchen Fraser and Mead Lawrence won their share of medals in 1948 and ‘52, the depth in the team only started to shine heading up to the 1960 Olympics.

“We had, without a doubt, the best women’s team in the world,” said Meyers (now Tikalsky). “We were a powerhouse and we had great camaraderie. We were truly a team!”

In the 1959 season, the American women began to actually win as a team. A few weeks after the strong showing in Kitzbühel by the U.S. men and women, Snite won the Arlberg-Kandahar slalom in Garmisch-Partenkirchen, Germany.

The team then headed home for the Olympic Trials at the new Wildcat in Pinkham Notch, N.H., greeted by a bevy of journalists from the Boston Globe to the New York Times and Sports Illustrated. They all wanted to see the rising stars of the U.S. Ski Team.

The Olympic season kicked off with a continued strong showing for the American women in Europe. In January, a month before the Squaw Valley Olympics, Pitou finished second behind Austria’s Traudl Hecher in the Hahnenkamm downhill. Defying her pact with Snite, Pitou tied with Meyers for the Hahnenkamm slalom title. In Lenzerheide, Switzerland, Meyers and Hannah went one-two in giant slalom with Meyers going on to win the prestigious Coppa Grischa Trophy series (Davos, Lenzerheide, St. Moritz) ahead of Snite and Anderson, as Pitou and Hannah sat out with injuries.

February dawned with Snite showcased on the cover of Sports Illustrated with a Roy Terrell story about Those Pretty Girls with the Killer Instinct. Terrell described Pitou as “… a cross between your little sister, your girl friend and a rubber ball. She has blue eyes and a big dimple in her right cheek and is thoroughly feminine. She is also as tough as a coal miner and sometimes talks like one.”

Look out, Squaw Valley, here they come!

U.S. women center stage at 1960 Olympics

The 1960 Games proved to be an idyllic experience for Pitou. She was far more mature than her experience as a schoolgirl in Cortina four years earlier, though she admits she “was still wet behind the ears about everything except skiing.” The Olympic Village was her haven, with Disney shows for the athletes every night.

“It’s funny now to think back and how everything went off just perfectly,” she said. “We had 10 days of gorgeous weather and then it started snowing again. We just lucked out. We all thought it was Walt Disney!”

The men’s and women’s downhills were completely different courses in 1960. The women came off KT22, a prominent peak rising up from the base area. The men’s course started at the top of Squaw Peak (think Palisades), with essentially one big turn and carving its way completely across the mountain then down a gully into the finish with France’s Jean Vuarnet claiming the win, for the first time ever on metal skis.

The women’s course was far more interesting with a steep start, diverse terrain and a 90° hairpin corner just up from the finish that claimed a full third of the field. The perilous Airplane Corner was an icy introduction into the final stretch to the finish.

KT22, named by Squaw Valley founder Sandy Poulsen for the 22 kick turns it took her to ski down the steep face, became legendary. Today, you can still track down much of the women’s downhill. The men were challenged with the start of their giant slalom right down the steepest pitch – a race where American Tom Corcoran narrowly missed a medal, finishing fourth.

A few years ago Pitou revisited the fabled KT22 women’s downhill run. While you can still ski the course, over the years, many of the sections of the run have been relocated, including the perilous airplane corner – ‘oh, they said, that was too dangerous, we changed that,’ Pitou was told.

“It was terrifying standing up at the top of KT22, totally looking off the pitch at all those bumps,” she recalled. “I said, ‘holy sxxx, I did that?’”

The day of the women’s downhill dawned bluebird and sunny. Freshly-fallen snow blanketed the peaks – enough that officials worried about slides. Pitou drew bib number one so she was first out onto the course.

Skis on her shoulders, the American star walked from the top terminal to the start and was helped into her skis. “I felt fairly confident,” she said. “I had done very well in lots of races. But this was really important. I didn’t want to do it anymore after this. And when I pushed off, I felt that wonderful feeling about ski racing. Sport is about being free to be or do whatever you want. In the downhill, you can just go as fast as you want. Nobody can stop you. That’s how I felt about it. I just loved being able to go hell bent for election.

German-born FIS official Ernie Blake, who would go on to found the Taos Ski Area, was the starter. Pitou drew bib number one. Blake called out the commands. And the race was on.

“I couldn’t wait to go. I went out of there and said to myself, ‘OK, now it’s mine. All mine! I was so full of energy. I was thrilled to be doing it. And it was like another world for me.”

She was skiing a flawless run. As she approached Airplane Corner, she set up for a high line as they had trained. Then she hit the ice and the rut. “I came as close to falling as you can without going on your face,” she told Sports Illustrated’s Roy Terrell. “I think only willpower kept me up. If this had been anything but the Olympics I know I would have gone down.”

Pitou’s friend Snite crashed, as did Meyers, who was still able to finish.

In training runs several days earlier, the American women had found a much faster line. While many took an inside direction on the corner, Pitou and her teammates found the outside line to be much faster. With heavy snowfall after the last training and no pre-race inspection that morning, the skiers went into the race blind and unaware of a deep rut that had developed.

“There was no radio communication then,” said Meyers. “I think Dave Lawrence (coach) was at Airplane Corner but he had no way to tell us.” Lawrence was nursing a broken leg at the time so even hopping a lift and skiing to the start was out of the question.

In the finish, all Pitou could do was wait. Germany’s Heidi Biebl started eighth. A month earlier, Pitou had edged her by over a second in the Hahnenkamm downhill. But Biebl was clean through the Airplane Corner, giving her enough cushion to take gold by a second with Hecher third.

After an interminable wait in the finish, the number one-starting Pitou was finally able to celebrate her silver medal. CBS was carrying live coverage across America. Doing the finish line interviews was Pitou’s mentor, Andrea Mead Lawrence.

“Here is this woman who I personally credit with my being here, and she’s interviewing me?” recalled Pitou. “I was just thinking, ‘wow, they’re all watching this on the east coast right now.’”

The storybook Olympics continued for Pitou. A few days later she won silver again, finishing second in the giant slalom to Swiss Yvonne Rüegg.

Life after ski racing

Pitou retired from ski racing after the 1960 season, heading back home to New Hampshire.

In 1961, she married Austrian downhill star Egon Zimmermann, who she had met at the Hahnenkamm in 1958. Zimmermann, who died in 2016, grew up in Kirchbichl, not far from Kitzbuehel where he finished second three times in the fabled Hahnenkamm.

They built a home just across the street from Penny’s childhood residence on Potter Hill Road. Together, they were a dynamic skiing duo, running ski schools at nearby Gunstock and Blue Hills in Massachusetts and raising two sons, Christian and Kim, in a German-speaking household.

“Egon was a very good businessman,” said Pitou. “And he was a terrific technical skier. We both became certified professional ski instructors. I think he got the highest marks and I got the lowest, but I still got to be one.”

Originally known as Belknap Mountain Recreation Area, a depression-era Work Project Administration development, it was renamed Gunstock in 1959 and was thriving. New lifts came online in the 1960s with Penny and Egon’s ski school in her childhood backyard. Celebrities from around the country found their way to Gunstock for an opportunity to ski with Olympic star Penny Pitou.

They introduced their own children, Christian and Kim, to skiing at an early age. “Mom was very driven,” laughed son Christian. “She wanted to be out in the mountains getting exercise 24/7 – skiing, hiking, tennis (she won a state title) – she was always doing something.”

The boys learned German early – their father spoke no English at the time. Christian became great friends with the Austrian ski instructors as a young boy. They would have fun tossing him around and throwing him into the huge piles of fresh snow.

At the end of each ski day at Gunstock, Penny and Egon would bring Christian to join the après ski fun at the Arlberg, a legendary restaurant and inn built by an Austrian, shortly after World War II. “I was so little at the time so I could run around under the tables pretty easily,” laughed Christian. “I remember lots of noise, lots of smoke and lots of German being spoken. I don’t remember any English”

As a young boy, he had little knowledge of his mother’s Olympic fame. And it didn’t matter. “I eventually learned about the Olympics and my mother’s success – my friends would talk about it,” he said. “But as a kid, you just wanted to feel comfortable and secure. My mom was my rock – I always felt taken care of.”

In the summertime, the family would hike – oftentimes to New Hampshire’s White Mountains. Over the years, they visited pretty much every peak and every hut. There were European ski trips in the winter and hiking trips in the summer.

After Penny and Egon divorced in 1967, she found a new life calling in Penny Pitou Travel, a company that evolved out of her love and passion for Europe and the Alps.

“After we separated and then divorced, I didn’t know what to do,” said Pitou, then in her 30s. So she went to a local career development school to find her path. “They asked me what kind of life I wanted to lead, what are your interests? I listed everything and they said, ‘well you can be a forester, you can run Outward Bound programs or you can be a tour guide.”

As luck would have it, a local travel agency was for sale. So in 1974, she launched her new career.

In the summer she led hiking trips, taking guests along mountain trails to alpine huts. In the winter, she revisited her favorite ski resorts, blending skiing, food and culture.

“Penny is just not a normal human being,” laughed one of her best friends today, Pam Merrill. “She has great energy, tells wonderful stories – I admire her greatly.”

Merrill met Pitou in the ‘90s after her husband, longtime nordic coach Al Merrill, passed and she was looking for a guided trip to Europe.

“Penny’s tours were a re-awakening for me,” said Merrill.

From Val d’Isere in the French Alps to the Selle Ronda in the Dolomites to the

Franz-Senn-Hütte in the Austrian Stubai, Pitou’s tours opened doors for hundreds of guests. Her attention to detail and local knowledge provided life changing experiences.

While she may have slowed down a bit, she continues to lead tours – COVID willing.

Proud grandmother

Today Pitou channels her pride to granddaughter Zoe Zimmermann. “You know, I am very proud,” she said. “I can’t believe it’s happening that I should have a granddaughter who’s going through exactly what I went through 60 years later.” Pitou is quick to point out the differences, too. Like when she went to Junior Nationals with one pair of Northland skis. Zoe went to Junior Nationals two years ago with 11 pairs of skis, a team of coaches and, in Penny’s words, “wonderful ski outfits.”

“Anything can happen, believe me,” she cautioned. “But she’s very quick and strong. She has very quick feet. That’s her specialty at the moment.”

Pitou loves to see her progress. But admits to being a scared grandmother with speed events. She’s proud of her connection with Dartmouth and her group of friends.

Zoe is a daughter of Penny and Egon’s son, Christian. She and older brother Zane are no strangers to skiing in the tracks of their grandmother. While the entire family is athletic and competitive, Zoe really stood out and found the same passion as her grandmother for going fast on skis. To Zoe, born 42 years after the Olympic medals, Pitou was first and foremost her grandmother.

“I didn’t really think of her as anything more than my grandmother who was really athletic,” said Zoe. “When I look back on it I just remember her being super active. She would come on hikes with us and ski with us. She would always keep up. It’s crazy how in shape she was, I aspire to be as active as her.”

Zoe can’t recall those early ski outings in the Alps when she was two, but her memories of ‘omi’ on high alpine trails later are vivid. “I remember skiing in Europe with omi,” she recalled. “We would go on her trips – more in summer – Switzerland and Austria. She took us to the base of the Matterhorn. We skied the Valluga (in St. Anton) – it was really steep. She talks a lot about being in Europe and just loving the culture and not being at all homesick.”

Penny has a treasure trove of stories of skiing with her grandchildren. “A few years ago I was skiing with my son Christian and his kids on the Rendl in St. Anton. I had finally gotten ahead of Christian. And I could hear him turn for turn behind me. I was making these big GS turns and I looked back – it wasn’t Christian, it was Zoe! And she was only eight?”

One night on that trip to Lech and St. Anton, local guide Klaus came to the group and said, “tomorrow we’ll take the kids down Valluga.” Penny gasped – she had never skied the legendary piste, much less send her grandchildren down. As Zoe’s father Christian tells the story today, Klaus was entirely confident in the kids, who were eight and 10. They skied turn for turn with the guide down the steep pitch – at times over 70% – making a critical left turn in a no-fall zone and skiing safely down. As Klaus tells it, “I’m pretty sure there was another 10-year-old who skied Valluga, but Zoe was the first 8-year-old.”

Talking to Zoe you sense the same passion for the outdoors and sport as her grandmother. “She’s always instilled in me that ski racing is 90% mental. It’s how you approach the day. I’m thankful for that.” Zoe’s goal this season is to make the Junior Worlds team, looking to get the start she missed when the pandemic canceled the event last spring.

When she was eight, Zoe and Penny rode a lift up KT22 at Squaw Valley to look at the course where omi won her Olympic downhill silver a half century earlier. “It was really soft and powdery that day,” she recalled. “I just remember falling and looking back up to her.”

What really happened in cortina?

So, what really led up to that chance encounter with Andrea Mead Lawrence that changed Pitou’s life back at the 1956 Olympics in Cortina?

In the Olympic downhill, she had a magnificent run going, just as Mead Lawrence had seen an hour earlier. It was a big event and the very first Olympics where there was some live television. Pitou wanted to look good for her mom and friends back home, not to mention for the dreamy Toni Sailer who was standing at the finish (they had dated).

“I got near the finish and thought ‘I want to look good,’” recalled Pitou.

So she got distracted – a momentary mental miscue that sent her careening down a steep face and into a transition where she landed on her backside, then her face and came spinning across the finish with her skis up in the air. She walked away embarrassed.

Oh, and Toni Sailer never asked her out again.

What winning is all about

Sixty years after leaving Squaw Valley with a pair of Olympic silver medals, Penny Pitou still has passion for her sport. She still lives on Potter Hill Road. Much of the old Gilford Outing Club hill is developed, but tubers and sledders still make their way down Bone Crusher when there’s enough snow.

She sees a lot of herself in Zoe. And she watches the stars of the sport today – a sport quite different from the one she mastered in the ‘50s.

“When I meet people, when I talk to kids and watch them, I can tell if they’re going to do it, if they can’t do it or if they won’t,” said Pitou. “It has to do with what’s between your ears. I feel 60 or even 80 percent of winning is from the neck up.

“It’s the ones who stay out a little longer, or who say ‘no, I’m not satisfied with that – I’m going to do it again.’ You know, the ones who really work at it.

“That’s what makes a winner.”

Penny Pitou has had a rich and full life, exploring the world and living out the passion she found hanging out with her friends as a kid in Gilford. When asked what it all means, she pauses only for a moment.

“What I’ve taken away is simply a way of life,” she said. “Skiing is my life. When I get on skis today, no matter how rickety I may feel, I never feel as comfortable and safe as I do on skis. Skiing has given me wonderful recreation and a way of earning a living. I’m at the office when I’m in Europe.

“It’s taught me a lot about myself, too. And I hope the people who have skied with me feel good about challenging themselves.”