Soul of World Pro Skiing Tour Paul Carson remembered by friends and family

In January, 1973, the World Pro Skiing Tour came to Collingwood, Ont. for the Benson and Hedges Pro Ski Classic. It was a star-studded field on the escarpment along the Georgian Bay of Lake Huron with the likes of Spider Sabich and 1968 Olympic triple-gold-medalist Jean Claude Killy — all vying for a $40,000 purse.

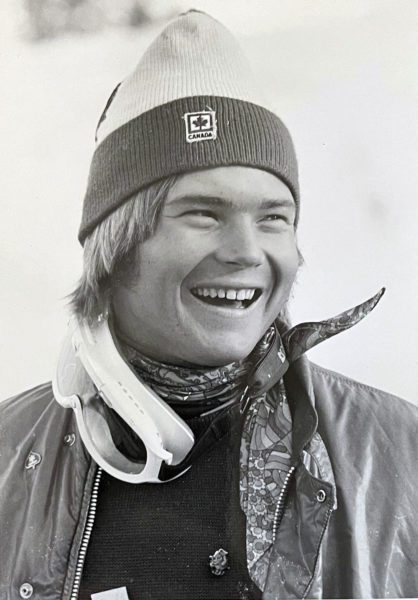

As race announcer Greg Lewis stood in the finish calling the action, a cherub-faced young ski racer slid up to him, waiting politely for a pause in the action. “He skied up to me and said, ‘Hi, I’m Paul Carson. I’m leaving the Canadian Ski Team, and I want to race on the pro tour,’” recalled Lewis. “He had a distinctive, child-like voice that resonated with inexhaustible enthusiasm.”

The world of ski racing was like the wild west in the 1970s, with racers from around the world gravitating to Bob Beattie’s new World Pro Skiing Tour. Heroes were made in the new head-to-head pro format, but it was the athlete personalities off the snow that gave the tour its charisma. One of the colorful characters who was at the heart of that culture, Canadian Paul Carson, passed away unexpectedly June 5 at his home in Ketchum, Idaho after a 14-year battle with cancer. He was 68.

Carson’s passing brought back memories of a period of time that was arguably one of the most dynamic in the sport’s history. Over the span of a decade, young men from every corner of the globe gravitated to the pro tour in search of fame and fortune. Many found fame, a few found fortune but all of them found lifelong friendships.

Paul Carson’s life was a deep-seated love story emanating from a tour that brought diverse personalities together and created joyful relationships. It started with the love of the outdoors and the love of speed that all skiers enjoy. Carson was the glue that bound them all together, serving as the nucleus for an eclectic group of characters. Nearly a half century from the time he first stepped into the starting gate, those friendships are still enduring.

In many ways, his life epitomized the culture of skiing itself, a lifelong family sport where like-minded enthusiasts share the same exhilaration of being on snow.

In true entrepreneurial fashion, Carson parlayed his youth as a Toronto ski racer into becoming one of the most popular athletes on the tour. He eventually took over management of the pro tour, before evolving his company, Carson International, into a global events business that introduced the world to beach volleyball, built a snowboard run on a Caribbean island and brought millions of viewers to upscale dog events.

From humble beginnings to the pro tour

When Carson came to Collingwood for that 1973 race, he brought along passion and an engaging smile – both of which would become hallmarks of his career. Carson wasn’t quite old enough to meet the tour’s 21-and-older standard, but he would be soon. And true to his promise, he made the tour his home, with his first start later that year in Australia.

“Paul would distinguish himself not just as a pro racer, but as a leader, an entrepreneur, and a man of grit and integrity,” said Lewis. “He was the kind of man you wanted as a friend. Even today, when I hear his name, I see his smile, I feel his warmth, I know, enthusiastically, his light will burn forever.”

A native of the Toronto suburb of Don Mills, Carson grew up racing out of the tiny 32-acre Don Valley Ski Centre, with high speed rope tows to whisk young kids to the top of the 200-foot mountain for the quick ride back down on their 215cm GS skis. He raced with buddies like Derek Robbins, whose father built the ski area, on the Don Valley Racers (DVR) team. Carson joined Robbins on the Southern Ontario Ski Zone team, moving up quickly through the ranks.

“He was one of the most determined and good persons I’ve known,” said Robbins. He tells the story of going to Cervinia, Italy as 15-year-olds with Porko, as Carson was known, as the top racers in Ontario. After the camp they spent a month hitchhiking around Europe, trying to communicate with young girls along the way who didn’t speak any English.

He made the national team at 17 (the only DVR ski racer ever) and took the Canadian slalom title in 1973. It was the time of the Crazy Canucks on the World Cup downhill tour, and there was less love on the Canadian team for technical skiers. Still, he raced across Europe, North America and South America. But he set aside the white circus of the FIS World Cup for a shot at global glamour on the World Pro Skiing Tour, bouncing from Australia to Aspen to Austria in a new format he found to be more attractive for fans and more fair for athletes.

It was a pioneering time for the sport. Just a few years earlier, in 1967, Beattie had teamed up with journalist Serge Lang and French coach Honore Bonnet to start the World Cup tour, which was growing rapidly despite lacking one key component: cash prizes for athletes. Commonplace today, a prize purse didn’t come to the World Cup until the 1990-91 season.

With the advent of the World Cup in 1967, combined with Killy’s triple-gold at Grenoble in 1968, the popularity of ski racing was growing. But with Olympic amateurism rules and the lack of cash prizes on the World Cup, Beattie saw a new opportunity. So in 1969, he created a competing tour and a formidable opportunity for ski racers with the start of the International Pro Ski Racers Association and the World Pro Skiing Tour.

The new circuit caught on quickly. Within a few years, athletes from most of the leading nations began bolting from the World Cup to the new pro series.

Carson followed his childhood buddy, fellow Canadian Doug Woodcock from the Oshawa Ski Club, traveling the world together both as competitors and friends. “We met at a dryland training camp,” recalled Woodcock, who was a year older. “At first we were mostly rivals. But we became buddies.” That friendship born out of ski racing lasted a lifetime.

“Those early years on the World Pro Skiing Tour were really fun,” said Woodcock. “But part of it was the opportunity to make some money!”

The allure of pro ski racing

Money was, indeed, the initial allure for Carson. But it went much further. He understood the marketing angle Beattie was seeking. The pro tour was not just ski racing. It was choreographed entertainment. It was custom built for television and for a new wave of commercial sponsors from banks to car companies to sunscreen and, yes, even cigarettes.

“Paul was what I would call the soul of the tour in a way.” said Norwegian ski racer and University of Denver star Otto Tschudi. “He had a very charming way of being outgoing and he understood the business.”

The pro tour featured a head-to-head format, which Carson found to be much more fair than skier after skier digging ruts on the World Cup. But it wasn’t just the paycheck at the finish line. It was the inherent attention on television and in news media, which ultimately led to paid endorsements – something not permitted in the Olympics or the World Cup tour.

What really set Beattie’s tour apart was its focus on the character stories of the athletes.

“He recruited racers who had a great story to tell,” said Woodcock. “You were independent. You were part of something that was new and growing. Beattie encouraged the racers to be colorful and to have fun. That was part of what he thought the tour needed to grow.”

Carson quickly stood out with a beach boy look and a captivating smile. “Paul was blond, handsome, very outgoing,” said Woodcock. “He always took his guitar with him and was quick to pull it out and play. That guitar was a weapon of mass seduction.”

Woodcock matched Carson’s guitar with his own banjo. The two of them provided background entertainment on the tour, playing bluegrass in gasthofs and pubs around the world and creating yet another component that became the fiber of the pro tour.

He found a real home there, finishing as high as third in the season rankings. He left the tour in March, 1981.

For journeyman ski racers, Beattie’s tour was so much more than ski racing. In a way, it was an MBA education on the tour. “Bob taught us how to deal with the business world at the same time we were having a great time racing,” said Tschudi.

From sponsorship to wedding bells

Carson understood that business model and his popularity quickly grew. Sponsors loved his dashing, handsome looks including that captivating smile.

In its early years in the 1970s, Colorado’s Copper Mountain supported events and athletes to help it stand out from a growing number of ski resorts in the Rockies. It brought Carson on as one of the faces of the resort, and the Canadian made it his home base.

He connected on a major sponsorship deal with Hawaiian Tropic. Entrepreneur Ron Rice had just started the brand a few years earlier and focused his marketing squarely on sports. But it wasn’t all football and basketball. Motorsports and ski racing were big targets for him, with skiing playing a huge role in the early brand promotions.

Rice invested heavily into the pro tour, sponsoring races and using Carson as his poster boy. He was an ideal fit, with his bleach-blonde hair and tanned face gracing the pages of national magazines.

At the same time, Copper Mountain brought on a young aspiring tennis pro, Kathy Murphy. As a pro skier Carson had played a little tennis. But when he caught a glimpse of Murphy, he decided he needed a lesson.

“He was a great athlete, but he could not play tennis,” recalled Kathy. “He was very competitive. But, to be honest, he probably did it just because he wanted to meet me. But it was pretty funny because I knew his background.”

Copper Mountain provided an unlimited playground of recreation for the two. “One of the beauties of our relationship was that we were both professional athletes and we did everything together,” she said. “We ran together. We trained together. We played tennis. We hiked.”

While she was admittedly not a great skier, she was willing to learn. And that’s when things almost went awry. Paul hooked her up with a pair of 190cm skis and loaned her a pair of pants.

The first time he took her skiing she fell on the first run and blew out her knee – just as Copper Mountain founder Chuck Lewis rode overhead in a chairlift, looking down at his resort’s ski ambassador with his fallen tennis pro and shaking his head.

But despite her unfortunate skiing debut, she was still smitten by Carson. She set aside her dreams of playing on the women’s pro tennis circuit to join him on the World Pro Skiing Tour. Together, they traveled the world.

“I went with Paul – I was the girlfriend and that was how we traveled,” she said. “We didn’t have a lot of money but it was just one of the most beautiful, fun times of our lives. The tour affected a lot of people like that – they built relationships.”

They took life as it came at them on the circuit. If he was in the money, that was great. If he didn’t qualify, they just hopped in their station wagon with their dog and headed out to the next race. It was a nomadic lifestyle interspersed with high moments of adrenaline on the race course, and hanging out with friends at ski resorts.

“I fell in love with Paul immediately – it wasn’t a year, it was like days,” said Kathy. “We had an instant connection because of the stuff we did together. And that built our relationship as best friends. That’s what we were! We were best friends because we had so much in common – because we were both athletes.”

A short time later, on Sept. 1, 1979, they were joined by family and friends at the patrol shack atop the Continental Divide at Copper Mountain for their wedding. Lewis had long forgotten the blown knee and rolled out the red carpet for the Copper Mountain couple.

The tour takes a turn

With the success Beattie was having with World Pro Skiing, it was natural that competing tours would begin. The most formidable became the Peugeot Grand Prix, a series that was formed in 1976 by Maine restaurateur Ed Rogers. Rogers, his partner Mike Collins and others started regional tours around the country.

In April, 1981, Beattie reached a crossroads with World Pro Skiing after the season finale at Mammoth Mountain where several athletes created a protest and blocked the starting gate. The next week, he took a step away from the tour, leaving athletes wondering about their future.

With hopes of returning to the glory they had found in the ‘70s, racers turned to Carson, Woodcock and Tschudi to recreate the pro circuit.

“We wanted to do a racing alliance,” said Tschudi. “But of the three of us, Paul was the only one who didn’t have a job right at that time. We said, ‘OK, Paul, you’re the president.”

Carson dove right in, serving as executive director of the new Professional Ski Racers Association. They opened offices in Copper Mountain and Saas-Fee, and that summer announced an ambitious tour with 15 races.

But the landscape was challenging. Sponsors were confused about the sudden closure of Beattie’s tour and there was competition from others, notably Rogers’ Peugeot Tour. Carson was successful in bringing on longtime Winter Park race sponsor, First Bank of Denver, but rebuilding the tour back to its same level would prove to be a challenge.

“In all the competition over the years of the pro tour, Paul Carson was probably the best guy I went up against,” said Rogers. “He knew what he was talking about, he worked hard at it and had the right ideas. I respected him a lot for it.”

After three seasons, Carson turned his business attention elsewhere while the existing regional series’ consolidated to keep the pro side of the sport going. Despite his move into other sports, Carson always had pro ski racing on his mind.

From the mountains to the beach

While the landscape of pro skiing was changing in the early to mid ‘80s, the company Carson formed with wife Kathy was evolving quickly. A colleague invited them to southern California to see little-known beach volleyball. It was the perfect fit for Carson International. The Carsons showed their brand prowess by connecting Jose Cuervo with the burgeoning new sport.

Together, Paul and Kathy introduced the world to beach volleyball, utilizing the same storytelling Paul had learned on the World Pro Skiing Tour. It was an exciting lifestyle sport played out on idyllic beaches with fascinating personalities.

“We were invited to LA to experience the sport of beach volleyball which was getting more popular,” recalled Kathy. “It was very disorganized and the guys were a little rough. We ultimately took a sport that was lighting up its courts with car lights all the way to the Olympics!”

Carson took his lessons from Beattie’s playbook, educating the athletes on their public presentation (no swearing), enhancing spectator access with bleachers and electronic scoreboards plus bringing the world to the beach through television. They moved the Carson International offices to Manhattan Beach, but eventually missed the mountains so they returned to Sun Valley. The resultant exposure they built helped the sport grow into the $750,000 Cuervo Gold Crown Series and its Olympic medal debut at Atlanta in 1996.

The Carsons were geniuses at connecting brands with the public. In the leadup to snowboarding’s Olympic debut in 1998, they brought snow and prospective Olympic athletes to the tiny island of Cuervo Nation in the Carribean for a stunningly successful media event.

But the big hit for the Carsons were dog shows. While working on the 1998 Super Bowl in San Diego, they saw an opportunity for dog challenges coming out of a halftime frisbee event.

Over the next 20 years they would become man’s best friend in canine Olympic-style competition, eating up big ratings on networks with their Purina Pro Plan Incredible Dog Challenge and the National Dog Show presented by Purina with 27 million viewers each Thanksgiving on NBC.

Taking another page from the pro tour handbook, the Carsons looked for ways to bring unique excitement to their dog events. Knowing skiing as they did, they opted to bring in notable ski announcers to convey a more realistic sense of competition.

“Paul was a brilliant visionary,” said Olympian and world champion freestyle skier Trace Worthington, who has been the broadcast face of Carson International’s dog events for 15 years. “They wanted to bring a bigger sense of sport to the dog challenge events.”

Worthington was quick to call out the family aspect of the Carson International production team. “Paul was the kind of guy you just loved working for,” he said. “It was a big family.” And, together, they brought an entirely new genre of sport to television.

Bridging pro skiing to the future

While Carson’s pro tour venture didn’t carry on exactly as planned, in many ways his work became a bridge to the future.

“Paul was really a mainstay of today’s pro tour, both as an athlete and a business leader for the tour,” said World Pro Ski Tour President and CEO Jon Franklin. “Paul was a big part of the pro tour culture in the ‘70s and ‘80s that we still honor with our tour today.”

Today’s World Pro Ski Tour shares a lot in common with its predecessor. It still showcases a blend of renowned champions, like Olympic gold medalist Ted Ligety, along with a collection of passionate young ski racers who have a unique story to tell. Many of them are just like Paul and Kathy Carson, loading up the truck after a tour stop and heading to the next resort.

Today’s World Pro Ski Tour shares a lot in common with its predecessor. It still showcases a blend of renowned champions, like Olympic gold medalist Ted Ligety, along with a collection of passionate young ski racers who have a unique story to tell. Many of them are just like Paul and Kathy Carson, loading up the truck after a tour stop and heading to the next resort.

“Personalities built Bob Beattie’s World Pro Skiing Tour to success in the 1970’s. Paul Carson was a vibrant thread in that fabric,” said Bob Beattie Ski Foundation Chairman Mike Hundert. “His athleticism was matched by his loving smile and affable personality. His kindness exceeded it all. We have lost a friend and family member of pro ski racing whose life had a profound impact on so many, who infused joy and laughter all along the way.”

More than 50 years after the start of the tour, the Bob Beattie Ski Foundation has served as a rallying place for the alumni of the tour. It supports causes in the sport and is an investor in today’s World Pro Ski Tour.

In December, 2018, many of the top pros from the tour gathered again in Aspen to celebrate Beattie’s life.

Carson, too, was a regular at Vail/Beaver Creek’s Korbel American Ski Classic, where everyone wanted to be in Paul’s team. “While there were always racers with more hardware and titles, Paul Carson was always the favorite team captain,” said longtime Vail Valley Foundation President Ceil Folz. “That sort of says it all. He had a fantastic ski racing career, but an even better run as a human being with his kindness and friendliness to all who he met.”

Battle with cancer

In 2007, Carson’s life took an abrupt turn when he was diagnosed with cancer. After experiencing breathing problems while bike riding, he went in for a checkup. He thought it was asthma. But it was lung cancer. And it had spread.

After an initial exam, the doctor came back and told Carson he had stage four lung cancer. He asked the doctor, ‘how many stages are there?’ The doctor replied, ‘there are only four.’ In calm, quick-witted fashion, Carson asked, ‘well, do you have any good news?’

Just like everything he did in life, he attacked cancer with passion – and with dear friends at his side from day one.

Tschudi, Woodcock and others used their network and knowledge to help steer their lifelong friend to the best support. He initially found it with Dr. Mark Kris at the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York. Despite the cancer wracking his body, aggressive treatments seemed to work. It went into remission, albeit with reminders that it was still there.

“We would talk every Friday for 14 years after he got cancer,” said Tschudi. “Paul was definitely … he was my soulmate.”

Despite the odds, he attacked the disease with a vengeance for years. “He lived a long time – riding his bike every day. He was a warrior,” said Kathy.

Just a week before his death, he had a good checkup and had been starting treatment at National Jewish Health in Denver. Signs remained positive.

On a warm spring Saturday in early June, sitting on his patio in Ketchum overlooking Baldy, Carson crossed the finish line for the final time. In the days since, an entire generation of ski racers have reconnected in his memory.

His office in Ketchum captured his life in sport with a collection of trophies and posters. He still stayed in touch with some of his World Pro Ski Tour friends from the ‘70s and ‘80s. While his career took him to beaches and arenas around the globe, he held close those memories of rocketing off pro jumps by day and strumming his guitar by fireside at night.

His office in Ketchum captured his life in sport with a collection of trophies and posters. He still stayed in touch with some of his World Pro Ski Tour friends from the ‘70s and ‘80s. While his career took him to beaches and arenas around the globe, he held close those memories of rocketing off pro jumps by day and strumming his guitar by fireside at night.

“Everybody was competitive back then, but Paul was one of the really good guys,” recalled Woodcock, who had been at his side since they first met at an Ontario ski camp. “He went out of the way to help people, even if he was competing against them. He was nice to everybody. He was a guy that people loved to be around, enjoyed being with and fun loving.”

While so many today are mourning Carson and expressing sadness that he left all too soon. Few would question the impact he had on others in his 68 years.

Kathy talked about the lessons Paul took from ski racing. He often spoke about the sense of serenity an athlete has in the starting gate at the fabled Hahnenkamm and the mental approach to put fear aside, always reacting to situations without conflict.

“Paul was one of the most creative men I’ve met – he could figure out anything,” said Kathy reminiscing. “And he would figure it out with calmness, which he had to do in ski racing. You saw that in his approach to beating cancer.”

But, most of all, what she saw about Paul Carson in reflection of his life was what he brought to others.

“I really believe that our meeting was one of those that was meant to be,” said Kathy reminiscing. “Together we’ve been able to make people happy, creating a little joy in their lives.”