Keeping it Fun — For Life

A guide for fixing the broken state of American ski racing

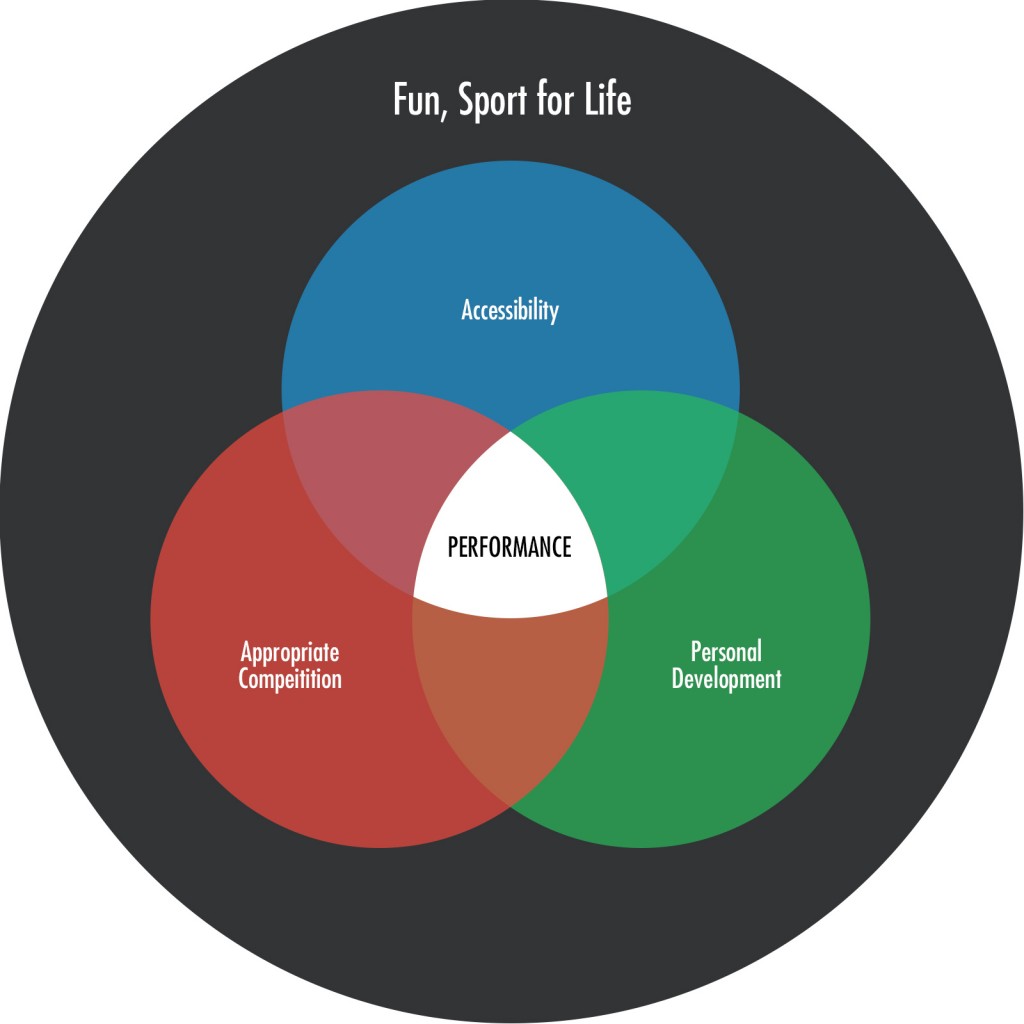

In youth sports, the “Three P’s” of Participation, Personal Growth and Performance can’t happen without fun.

Fun is the No. 1 reason athletes stay in a sport — or drop out.

Even the most elite World Cup skiers say they continue to “play” because they love the sport and because they’re having fun.

In surveys, most parents list the outcomes of personal development, life lessons, love of the outdoors and healthy lifestyles as the attractions of ski racing. Expense, too much time, pressure and risk of injury are often listed among the negatives.

A healthy sport will provide accessibility, appropriate competition, an opportunity for personal development all intersecting in performance — and all encompassed by fun, fulfillment and enjoyment for life.

But today’s ski racing system encourages too many athletes to pursue a “professional” pipeline, making it costly (time, opportunity, expense, etc.) to play the sport for fun, personal growth and improvement.

While an effective elite athlete pipeline is critical to identify and advance top performers with the ultimate goal of medals in Olympics and World Championships, nearly any athlete who is age eligible can currently pursue international competition regardless of whether they are competitive among their age or ability peers.

So the answer lies in creating a system where standards and performance-based advancement of athletes into increasingly competitive events and series will provide the necessary challenge to promote development while maintaining appropriate ability and age matched competitions for all. The majority of racers should be able to have the experience they seek in the sport. They should not feel forced to leave their state, division or region to remain challenged.

How to Create Appropriate Competition

We all naturally work harder to improve when we’re closely matched in ability with others. Multi-player gaming theory emphasizes pairing players of identical skills to create close contests and an addiction to the game. Professional sport leagues, meanwhile, create rules to equalize teams and encourage close contests. But when the outcome is known, both players and fans lose interest.

1. Reduce FIS racing

We need FIS points for seeding when athletes from multiple nations compete together. Important international rankings used for team selections rely on appropriate access to FIS races. For some, this begins with the first year of age eligibility. How can a reasonable standard of eligibility for FIS racing be determined?

A quick look at the 2015 FIS Base List shows that to be ranked in the first 50 boys or girls in the world at the conclusion of the first year of FIS eligibility (year of birth, or YOB, 1997), you need about 50 FIS points in slalom or GS. (Super G and downhill are less reliable as an accurate ranking because of the fact that young skiers around the world have unequal access to speed events.)

In the next birth year (1996) the standard for top-50 rank is approximately 35 points in slalom or GS. (YOB 1996 athletes have had three years of FIS experience as a result of the age change)

While many athletes, especially boys, will become competitive at the highest level after entering the top 50 for their YOB somewhat later in their junior years, it’s hard to imagine that this possibility requires that all athletes should be qualified for FIS racing when they become age eligible.

One could argue that a standard for access to FIS racing for first-year FIS eligible athletes of 75 USSA points in slalom or GS, and 60 points for second-year FIS age athletes, would serve to identify those athletes who “need” access to FIS points in those ages. An increasingly higher standard for U21s and Seniors would be appropriate.

Regardless, we must decide what level of performance legitimately qualifies an athlete to participate in FIS racing. Filling the field with the next available competitor, if not qualified, serves neither the athlete nor the sport.

2. Coordinate a national FIS calendar

We need to plan more strategically around internationally sanctioned races. Coordination of the NorAm, FISU and Regional FIS calendars will eliminate the “attractive nuisance” of chasing “point opportunities” across the continent. Focusing on Regional FIS Series will allow for more planning, less travel and better periodization to enhance development and reduce expense. Quotas to visiting regions should only be offered to designated events to create head-to-head opportunities for the best from each region to come together one or two times a year. The total number of FIS races calendared in the U.S. could be halved while still providing appropriate opportunities for those who are ready for them.

3. Place emphasis on USSA races and points

With FIS racing limited, USSA racing will become the emphasis for the majority of athletes. Multiple levels of ability-matched competition will provide appropriate competition and opportunity for performance-based advancement. And a return to using USSA points for selections and seeding of championship events such as the U18 Championships will further validate USSA racing.

Equipment specifications remain a challenge. Over time, this may become less of an issue as equipment specifications evolve. Regardless, if younger skiers are somewhat advantaged by their equipment, older skiers are advantaged by their size and experience. This shouldn’t be the “deal breaker” to staging USSA series where different ages compete together.

4. Establish rigorous standards for out-of-area competition

The compelling reason to race outside of one’s geographic zone is for the additional challenge among competitors who are at or near the top of their peer group. Top divisional athletes need to compete regionally; regional athletes need to compete nationally; and nationally top-ranked athletes need to compete internationally. Benchmarking our best with our international competitors is important beginning at U14. We cannot develop in a vacuum.

But elite international competition should be reserved for athletes who’ve either met an appropriate standard or who’ve qualified for a specific regional or National Development Project. Standards should be increasingly higher for travel to Canada, Europe or Southern Hemisphere races.

The cultural and personal-growth opportunities of racing and training in another country can be invaluable. But creating a culture in which any but the most highly competitive athletes view international travel as a must is damaging.

The risk in not establishing meaningful standards is that capacity, not performance, drives opportunity.

5. Encourage ability-matched competition and performance-based advancement

Early alpine sport pipelines hardly differentiated between seniors and juniors. Athletes were classified to a level of competition appropriate for their ability. The ski racing experience is defined by starting near the end, working up to the front, moving to the next level and starting at the back again. These multiple levels allow an appropriate competitive experience for all the athletes, pushing each to improve and creating achievable goals and stepping stones.

Matching competitors by ability and, for example, advancing the winner each weekend to the next class creates a healthy competitive environment. Selecting an individual or small number of athletes doesn’t de-motivate the remainder. The larger the number of athletes advanced, the less meaningful the achievement becomes, and the more discouragement is felt by those left behind.

Age-group championships have an important place in the progression. Gathering the fastest racers in an age group helps provide perspective and affirmation. Age matching should be the exception for junior and children’s championship events and not the rule for all competition.

How to Increase Accessibility

Sadly, there are many passionate, professional ski racing coaches, ski instructors, patrollers, other ski industry professionals and ex-ski racers who guide their children away from ski racing, realizing that costs can rapidly escalate to become unaffordable. Travel, fees, memberships, camps and equipment all cost more as the athlete gets better. Those successful enough to be selected to make the step to the national team are presented with a bill that is often larger than what they’ve been spending at their club or academy because of generous local support.

This is just plain wrong. Any economist will likely tell us that the financial incentives are misaligned.

Implementing the above suggestions will help to manage some of the biggest costs in the sport — excess travel to faraway competitions, too much racing at inappropriate levels, “defensive” chasing of points in order to not miss opportunities, and so forth.

Managing this unnecessary expense through application of appropriate standards and a clear pipeline has the potential to help accessibility significantly.

There are many additional ways, some presented below, to lower costs and improve retention.

1. Take full advantage of local resources

Time on snow is king. The least expensive time on snow is at home. So make the most of the time on snow at home.

It’s not unusual for young athletes to skip training or parents make other plans when the schedule calls for freeskiing. Every moment of time on snow is important “training” — especially non-directed freeskiing in a variety of terrain and conditions. If you’re not skiing, you’re not getting better.

Being the first on the lift and the last off the hill will add many hours of on-snow time over the course of a season. Taking advantage of every minute, every run and every day provides valuable reps without any incremental cost.

Snow and gravity are too precious to waste.

In every part of the country, skiing interest begins to wane and thoughts turn to summer activities before the snow has left. That leaves terrain open for the taking. Using every possible day locally maximizes critical on-snow time without paying for airfares, hotels, restaurant meals or off-season coaching.

After you’ve picked all the “low hanging fruit,” additional time on snow becomes more important. Fewer camps of the longest appropriate duration amortize the cost of transportation and reduce the daily cost. For all but the highest level athletes, there’s little justification in spending $2,000 on a plane ticket to New Zealand or Chile to be on winter snow instead of $600 or a van ride to train on spring or summer snow in North America. The former is an enriching cultural experience, perhaps. Critically more productive time on snow it is not. Sometimes the carrot of summer FIS racing is used to incentivize participation, adding unjustifiable expense.

2. Focus on slalom and GS

There’s widespread consensus that technical event skills are critical for long-term athletic development. Short-term results can be achieved in the speed disciplines, but long-term performance depends on solid technical development, experience and longevity.

An unintended consequence of the start limitation for first-year FIS athletes is to push some athletes toward more super G and downhill racing at a time during which the start limitation was intended to encourage training and maturation. Some illusion of success is produced by this tactic because of more limited participant numbers and inconsistent opportunities around the world.

There’s unquestionable value in speed training as a development tool. The increased speed of super G creates a search for speed in GS. The longer radius prescribed by the course allows athletes to feel a carving ski, sometimes for the first time. The thrill of learning to jump, and gaining awareness and comfort in the air, improves confidence and develops courage. All these benefits can be gained without unnecessary cost or excessive risk.

Downhill racing at junior levels is usually a hair-raising affair that does more to scare than thrill the participants. If our goal is to discourage kids from wanting to race at high speed, we’re probably succeeding. If our goal is to encourage racers, help develop necessary skills and create a passion for speed, the evidence that we’re failing is easy to find. Just review the start lists of any FIS downhill or, increasingly, super G. The question around what role downhill racing should play seems to be resolving itself. Racers, parents and coaches are voting with their lack of participation. Time away from school, opportunity cost, risk and additional expensive equipment to buy are all factors.

3. Simplify equipment, gear and wax

The equipment expense issue has been exacerbated by the FIS regulations and soon-to-be applied USSA equipment rules. “Hand-me-down” skis for downhill, super G and GS suddenly became unavailable in the used market as a lower-cost alternative. Taking last year’s “racers” and making them this year’s “trainers” has become impossible because of changings specs, sizes and rules. FIS giant slalom skis have become as specialized as jumping skis. Few pairs of these skis — which were once a staple of consumer sales — are sold at retail to recreational skiers, resulting in a higher price for racers. Formerly the freeskiing ski of choice for racers when not gate training, a different pair of skis is now the norm for skiing powder, groomers or ripping turns for fun.

Parents often obsess over waxes and base structures when greater effort or knowing which side of the start wand to favor or the most direct line to the finish usually has a greater impact on the time. Only when a skier is consistently able to carve clean turns; is skiing with urgency from start to finish; racing at a competitive level; and “needs” those last few tenths or hundredths of seconds does it begin to make sense to spend money on high-fluoro waxes, overlays and re-grinds for spring conditions — but even then, probably not.

Far more benefit comes from having consistently well-tuned edges every day; skis that are regularly waxed with less expensive hydrocarbon waxes; warm clothes; and a healthy snack in the pocket.

Some parts of the country have implemented no-suit rules for children or one-ski rules to address this sort of silliness. Nordic coaches recently voted in a three-wax rule in the Rocky Mountain Division for all Junior National Qualifiers so coaches could coach and so that athletes performances’ could reflect their conditioning and technique.

Whether rules or common sense are applied, there’s lots of discretionary spending on the sport that is unnecessary.

4. Build character development

At the end of the day, the most important outcomes from pursuing a discipline such as ski racing are not the wins and losses but the lessons learned from the process. Whether high school racer or Olympic champion, the life experiences that create who the individual becomes are what matter most. The friendships, memories and lessons last a lifetime; we soon forget the falls and podiums.

As the saying goes, “Sport doesn’t develop character, it exposes it.” Values such as responsibility, commitment, perseverence, work ethic and appropriate risk-taking that sport emphasizes serve athletic excellence and success in life equally.

What’s Next?

The aforementioned tasks can be undertaken in the near term to begin to fix some of the issues that have been identified. Some are small, some are large, and all contribute toward bringing reason into a system that has lost some of its sanity. That means accessibility, fun and excitement at the entry level, competition, personal growth and fulfillment throughout and performance focus where appropriate.

What if we had a do-over? If we started from scratch, what would the ideal design of a sport system from grassroots to Olympics look like? Next month, we dream a little.