Work With Me: Project 26 Could Use Some Project 22

As of last week, all of the major national ski teams have been named. With 30 athletes on its A, B and C teams, and no men’s World Cup slalom team, the US Ski Team wins the award for most difficult and most age-restrictive criteria. Powerhouses like Switzerland, Austria, Italy, and France have significantly larger rosters, beefy development squads and more lenient criteria at the high end. Even Norway, the model of stripped down national federations, supports 36 athletes on its World Cup and Europa Cup teams. Why are we so small and—considering our shrinking number of World Cup spots—so exclusive?

I was curious about this, and asked some questions. I talked to college, club, academy and national team coaches; to racers on the national team, racers freshly off it and alumni from many eras; to industry reps, sponsors, educators, insiders, outsiders and parents driven near crazy and broke by trying to do what’s best and healthiest for their kids. Not surprisingly, a complex picture emerged. Alongside a disturbing sense of resignation that things will never change, funding will never resolve and maturity will never warrant discretionary consideration, there is also an impressive sense of resolve—within and outside the national team—to keep trying to get it right, and above all to persevere nonetheless. The athletes closest to the team, and most drastically affected by the latest cuts are hurt, and disappointed but they are pragmatic. Athletes on and off the team want nothing more than success for their ski racing peers, and a fair chance to go after their own dreams. For them especially, I offer this bit of perspective of the current landscape, to help inform conversations that will hopefully lead toward clarity, and away from murk.

In my discussions and observations, two things feel conspicuously unresolved.

What about Project 22?

The small team tactic is part of a plan called Project 26, aimed at boosting development of medal hopefuls for the 2026 Olympics. The idea described in this Ski Racing article, puts more resources towards development while also keeping athletes in their home clubs and regions longer. It keeps costs down, raises the level of skiing across the country and we reap the dividends in eight years. That all sounds good, and indeed there are very positive reports on development initiatives. The flipside of increased development of younger athletes, however, is decreased support for the athletes who, just a few years ago, were considered top prospects, and who would be coming into their primes in the next four years. One might call those athletes Project 22. One might also call them the lost generation.

The small team tactic is part of a plan called Project 26, aimed at boosting development of medal hopefuls for the 2026 Olympics. The idea described in this Ski Racing article, puts more resources towards development while also keeping athletes in their home clubs and regions longer. It keeps costs down, raises the level of skiing across the country and we reap the dividends in eight years. That all sounds good, and indeed there are very positive reports on development initiatives. The flipside of increased development of younger athletes, however, is decreased support for the athletes who, just a few years ago, were considered top prospects, and who would be coming into their primes in the next four years. One might call those athletes Project 22. One might also call them the lost generation.

Looking at round birth years, the average age of individual Olympic Alpine medalists in 2018 was 26 for women, and 29 for men. Roll that forward to 2022, and the average age of medalists will be from YOB 1996 and 1993 respectively (with a 13 and 12 year range respectively). Our tech rosters include exactly 1 man and 1 woman born between 1989 and 1997, with zero men in SL. By ignoring the potential of athletes born in the early- to mid-Nineties we have “skipped an entire generation,” one person observes. Thanks to college racing and privately funded teams, many top athletes of that generation are still skiing and still improving, fueled by the sheer desire to ski faster… and are getting totally dissed. Meanwhile, our top national team SL men, born in ‘97 and ’98, are untested at the World Cup level. They are very talented, but that is a huge burden of expectation to put on some very young shoulders, especially considering all the American athletes above and around them on the FIS list who, if included on the national team, could help them mature. “This is the principal we live by at the college level,” said one college coach. “I have 24 year olds on the team with 18 year olds. They are all good skiers but the synergy is what makes it successful.”

The disregard for these Project 22s helps explain why support for Project 26 ranges from wary to cautiously optimistic. Is this simply clearing out the old, bringing in the new and setting a safely distant deadline to evade accountability, or is it a meaningful shift in philosophy? Anyone who has lived a few of these cycles, from the inside and the outside, has seen this movie. Blaming the athletes, getting rid of them, and starting fresh does not move the ball forward. On the plus side, Project 26 puts a premium on improving team culture, and cooperation between the national team, regions and clubs. Both are worthy aims.

WHAT IS “WORKING WITH?”

With such narrow criteria and funding for the national team, fielding our best ranked athletes in competition will mean “working with” non national team athletes. Acknowledging this interdependence is a key component of Project 26. Something struck me while reading World Class, Peggy Shinn’s book about the making of the US Women’s Nordic Team, and it was reiterated in conversations with the Nordic community: The turning point for US Nordic skiing was when the US Ski Team realized they needed to work with other programs. That first step led to true collaboration toward developing talent, whoever and wherever it was.

The concept of “working with” athletes, is vague enough to have many interpretations. It can be a sincere effort that benefits both the organization and the athlete; or, it can be an obligatory and meaningless gesture that broadens the gulf. It can mean full integration to a camp, a training block or a prep period; or, it can mean a last-minute booty call to a World Cup race with no support and no intention of a long-term relationship. “Working with” a World Cup athlete productively requires preparation, coordination of schedules, access to training venues, tech support, coaching and representation at races. It also requires access to the best equipment, a huge, hurdle for non-national team athletes. “Working with” college athletes largely involves providing supplemental, high level training and pace in the off-season when NCAA athletes are not allowed to train with their college teams. Here too, help with equipment and access to top level venues would be a huge benefit. “Working with” any level of athlete means welcoming them aboard when their performance warrants it, in a way that is intentional and truly inviting. These are all areas where the USST has a golden opportunity to walk the culture talk.

As one college coach says of developing as a ski racer through college, “Nobody said it’s easy or it is better than the national team, but you can do it and we will help.” College coaches remain positive and hopeful of collaboration, but also wary given the hot and cold history. Depending on who you talk to, the US Ski Team’s relationship with college skiers has historically fallen somewhere on the continuum between “embracing” and “ignoring,” mostly settling around “tolerating.” The National University Team experiment was one bold move towards embracing. Now these N-UNI athletes, ranging in age from 21-25—and their slightly younger female cohort— are poster children for Project 22. They are still improving and ready to commit with no distractions and the security of a college degree. None, however, are on the national team—not even Brian McLaughlin, who achieved the highest possible marker domestically, earning six FIS points and a World Cup start for next season.

At age 24 McLaughlin is “too old” to be considered under US Ski Team criteria (which he had no way to achieve domestically), but he is being “worked with,” and offered “full access.” First, what do those terms mean and what exactly do they include? Second, why is he not simply on the national team, when team status would give him access to the top equipment and preparation he needs to have the best, fairest chance at success? It would also send a positive encouraging message to kids. The average age of the World Cup first seed is 29. Why not let kids envision a future in the sport past age 17, and fan that flame with the brass ring of real opportunity? Setting impossible age-based standards snuffs out the spark before it can even ignite.

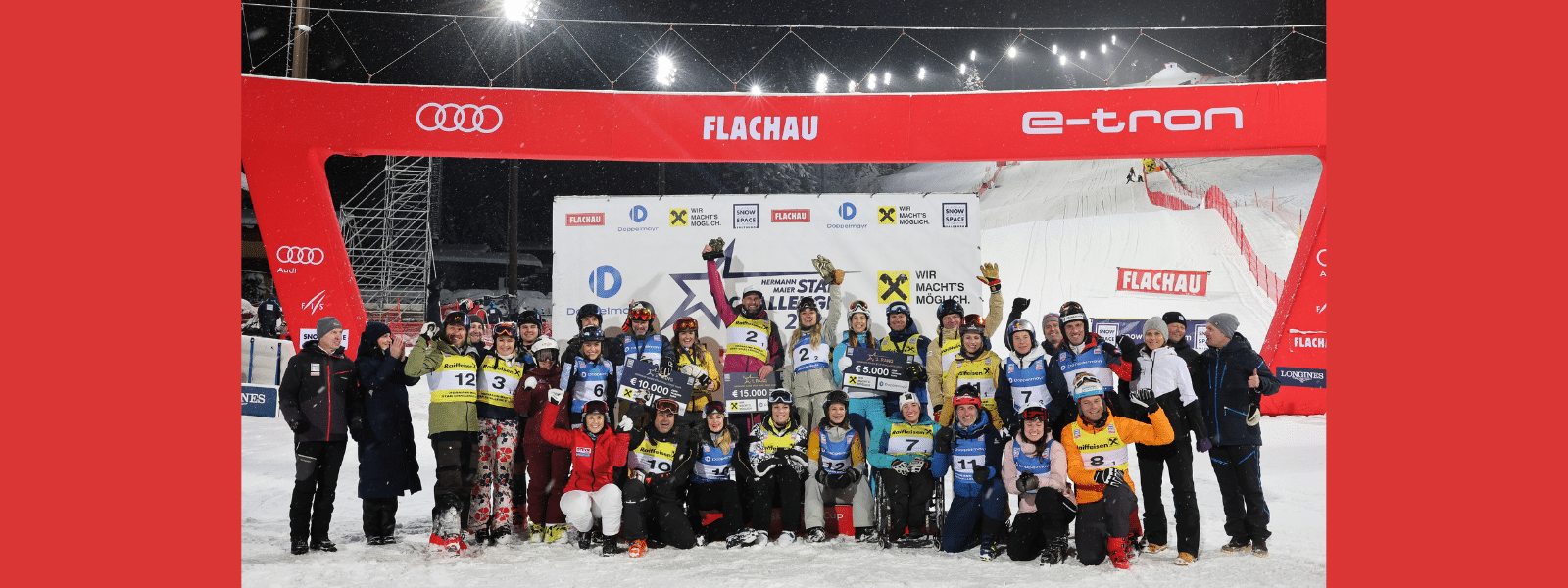

Lila Lapanja earned a World Cup start next season, powered by Team Clif Bar. Here, she races the night slalom in Flachau 2018.

SHIFTING CULTURE: In the words of Yoda, “Do or do not. There is no try.”

This summer the US Ski Team launched projects in conjunction with college teams, a very positive move towards collaboration. What will convince people that this shift is for real? “Fluidity,” said one athlete without hesitation. When the very best athletes—whether from college ranks or private teams—can move fluidly in and out of the team as needed and warranted, that will be huge progress. Any American qualifying or qualified for a World Cup, World Champ or Olympic spot deserves to be treated like a professional and not like a gypsy.

With fluidity in mind, I asked a number of coaches: “Would other top national teams take Brian McLaughlin?” A source directly connected to the Norwegian Team said, “For sure! And they’d be grateful to Dartmouth for developing him for free.” The Norwegian federation relies on talent developed outside of their national team, and are agnostic as to from where and by what age qualified talent is delivered. From a European World Cup coach: “If you have six points and a college degree you should be fixed on the national team.” As for McLaughlin’s lack of international experience he added: “Nobody really knows what he is capable of doing. It might be a pleasant surprise.” And that’s just it. If the culture is shifting, then now is the time to try something new and reach wider, rather than to get stuck on a thin base of statistics that are used to exclude. Now is a time to show a commitment to an inclusive, collaborative culture.

Ski racing development in Europe is just plain different—more competitive with less chafe. Geographical advantages make access to high level competition more accessible in every way, and many Europeans have the current and future security of government jobs provided to them while they are still competing. (Italy and France have some seriously fast customs agents and policemen!) Many more high level athletes stay active in their competitive ecosystems longer, which creates a development model we can never replicate. The US, however, has its own unique advantages; namely the USCSA and NCAA college racing circuits that keep more kids racing longer. We also have the entrepreneurial spirit and resources to fund private teams that are cropping up to fill demand. This is where Project 22 lives, even more aptly named because these uniquely American opportunities are helping keep as many kids in the sport as possible through the age of 22 and beyond. That broadening, more than any complicated winnowing strategy, will increase our chances of success.

GIVING MATURITY A CHANCE

Whether or not you believe in the wisdom of exclusivity, the practice puts a high premium on early talent selection. Top professional sports organizations don’t rely on that for development. The NFL requires players to be recruited from a college program, and to be at least three years out of high school. Those college years allow for and reveal the physical and mental maturity, and character, needed for the major leagues. Major league soccer teams all have their own pipeline to develop homegrown talent, but they don’t hesitate to pay top dollar (hello $200 million Ronaldo) for the very best players from other countries. If “Best in the World” is all about winning medals, then why not recruit and retain the best talent available, regardless of statistical age barriers?

There is no one right development path. Private teams, college teams and national teams are all part of our skiing ecosystem. We need to work together in a way that is intentional and collaborative, not proprietary. When that is happening from the top down, good culture will become more than a feel-good concept or a talking point. It will be a natural outcome, and the driver of the sport. Can it happen? Absolutely. Will it happen? We’re ready to see.